Dear Analyst #77: The top 3 mental models I never think about and live by (I think)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS

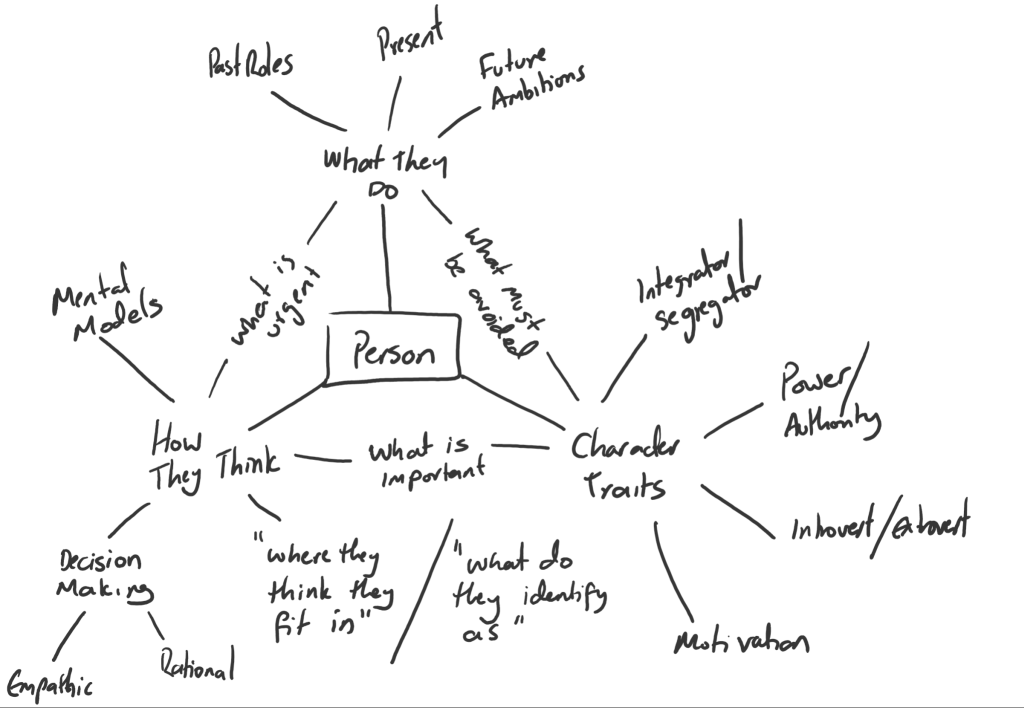

The promise of mental models is that it helps you bridge the gap between what’s in your mind and what happens in real life. They are interesting thought exercises in how you think. But that’s where it ends for me. How often do you approach a big decision in life and decide to pull from your little bag of mental models to make the best decision? Life (and the decisions you face) are messy. Yet, we see countless bloggers and authors provide their own takes on mental models (I’ve referenced Shane Parrish’s mental models multiple times, to be fair). An entire industry of leadership and career coaches use mental models to describe a person:

I’m sure this coach, does some great work with his clients, but something about having my entire being defined with a few lines and phrases doesn’t sit right. Perhaps mental models are best left for VCs and thinkbois on Twitter. The issue I have with mental models is that they are easy to write and talk about, but the examples people cite seem too farfetched and “clean” to work in real life. With that said, here are a few mental models I like to read and think about, but rarely use in real life (because life is messy).

1) Power laws and the 80/20 principle

The classic Pareto or “80/20” principle. No doubt this mental model has come across your Twitter timeline in the last week. Via Wikipedia:

The Pareto principle states that for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes.

Thinkboi thoughts on Twitter:

One example a really like from history is from WWI and a German fighter pilot named Manfred von Richthofen (aka the “Red Baron”). Unlike other fighter pilots at the time, Richthofen approached aerial combat with conservatism. This meant less aerial acrobatics and what you might otherwise see in Top Gun.

His fleet was constantly outnumbered by Allied forces and he knew if his men entered into combat head-to-head, he would always lose. Instead, he created a special formation for his fleet called “The Flying Circus.” This formation would just hammer the hell out of a specific point in the Allied’s defenses. This led to him taking down more Allied planes than he would have otherwise using traditional aerial combat techniques. In the context of combat, Manfred was able to 80/20 his results by taking advantage of the multiplier effect whereby one side can create outsized impact just from having a more numbers than the other side in a battle. I could be conflating two different mental models here, but the effect of dominating a small part the enemy’s defenses day after day must have a huge impact on their strategy and morale.

80/20 principle and data

Back in the real world where you have numbers to crunch and spreadsheets to format, how might one use this mental model at work? Again, I don’t actively think about using the 80/20 principle before I go and pull some data, but the simplest way for this model to manifest itself in a spreadsheet is sorting. What does this mean?

You’re doing some analysis and trying to find the key driver for why sales are spiking or why customers are churning. Pull the data you need and instantly sort on the column that contains your key metric. 80% of the time (see what I did there?), that simple operation of sorting the data set will help you find the answer you’re looking for because the product or customer that is driving the issue will show up at the top of your spreadsheet.

2) Recency bias

Perhaps not a mental model from a traditional definition, but something to have thinkboi thoughts on nonetheless. Via wikipedia:

Recency bias is a cognitive bias that favors recent events over historic ones.

I’m singling out this cognitive bias because of its impact you see in business, politics, and hey, your personal thoughts. For all the basketball heads out there, who do you think are the top 5 NBA players of all time? That list probably includes the likes of Jordan, Kobe, and Lebron.

Asking this question to a 20-something will probably yield different results than a 50-something. Why? Because you’re not seeing some of the greats from the 70s and 80s play regularly and in social media (unless you’re watching ESPN Classic). This means your benchmark for a “great player” is coming from the most recent 5 NBA seasons, maybe 10?

If you had to pick the top center of all time, would it be Shaq or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar? You think about Shaq’s run with the Lakers, his thunderous dunks, and 300lb+ body and may feel inclined to pick him just with those data points. What do you remember about Kareem’s career? Skyhook probably comes to mind. But dominating like Shaq? Maybe not. But if you compare the two big men’s stats from all their career games:

Kareem led in every major stat category.

Recency bias and investing

Outside of sports, you hear (and probably experience) recency bias in the investing world. Investors tend to give more credence to short-term results and pick funds and stocks based on recent information they have about the asset.

I think Bitcoin is a great example of this to a certain degree. If Bitcoin goes below $40K these days, hodlers may think Bitcoin is cheap and it’s time to load up the bags. One year ago (September 2020) Bitcoin was $11,000. Is <$40K still considered cheap or undervalued? Bitcoin’s presence and portrayal in the media only adds fuel to the fire:

Crypto may be a bad example, but apply recency bias to stocks and you’ll hear the rallying cry from Fidelity, Vanguard, and robo-advisors like Wealthfront. Diversify your portfolio, index funds, asset allocation, and their ilk. If you pick stocks individually, you’ll always underperform the S&P in the long-term, they tell us. I’m not saying the long-term strategy we’re being fed by brokerages and 401k plans is wrong, but it’s not 100% right either for every investor. Will save my rant on this for another time.

Recency bias and data

This may creep into recency bias’ sister: confirmation bias (finding facts to support your opinion). If you’re doing an analysis and remember that one of the key takeaways from last quarter’s BvA report was that supplier X drove the higher than expected expense, you may look to supplier X again to find the explanation for this quarter’s overspend.

It’s easy to turn to the most recent explanation to account for why something happened, but the correct method is to go farther back and take history into account in your analysis. Maybe supplier Y had an unexpected expense that is 300% greater than their previous expense 6 quarters ago. You wouldn’t know that if you didn’t look at the trends from more than a year ago.

Speaking broadly, the amount of data we have available today versus 5 or 10 years ago can lead to recency bias as well. If you have more granular and frequent data points getting streamed into your database, tempting to use these robust datasets to run your analysis. Just because your data from 10 years ago doesn’t have as many dimensions or granularity doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be included in your analysis for an important decision. Data from many quarters or years ago can still be accurate without being stale.

3) Hanlon’s Razor

I’ve written about this aphorism before (see episodes #47 and #38) in relation to Excel errors. Via Wikipedia:

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. It is a philosophical razor that suggests a way of eliminating unlikely explanations for human behavior.

It’s giving someone the benefit of the doubt that they were not intentionally trying to hurt you. They just didn’t know any better.

Christian Pham was a 40-year old professional poker player ready to enter the World Series of Poker in 2015. He had been playing no-limit Texas Hold ’em in St. Paul, Minnesota, and this tournament was a chance for him to make a name for himself. He signs up for the tournament, and eagerly awaits his seat at the table.

It’s game day, and he sits down at the table. He’s told the buy-in is $1,500. This is very strange, he thinks, since the buy-in for the Main Event (no-limit Texas Hold ’em) is supposed to be $10,000. Worry not, this must just be some snafu with how they collect the buy-in.

The dealer starts doling out cards and this is where things get really weird. He gets dealt 5 cards. His nerves really get strained now because you’re only supposed to be dealt 2 cards in Texas Hold ’em.

Christian signed up for the wrong event.

He accidentally signed up for a game at the World Series of Poker called no-limit deuce-to-seven draw lowball. He’s never played this type of poker in St. Paul, and he’s staring in awe at his 5 cards on the table.

Christian’s opponents at his table think Christian is bluffing. They think he’s pulling a fast one on them and pretending to not know how to play Kansas City lowball. If I saw a player at the table start to win hands at a game he claims to not know, I’d be a bit skeptical as well.

Christian wasn’t bluffing, and he really had no idea what he was doing. He didn’t know what strategy to use and was trying to piece together the game by talking to the dealer and some of the other players. Inexperienced poker players can sometimes be the most difficult to play against because they are effectively gambling while the pro players are employing every technique they have been taught to win hands.

The players at Christian’s table soon realized Christian really had never played the game. Being the rational (and human) players as they are, the other players gave Christian some tips on how to play the game to maybe remove some of the unpredictability from Christian’s style of play. Regardless, Christian ended up beating out 219 players and walked away with $80,000 from playing a game he didn’t sign up for.

Hanlon’s Razor working at work

I think that this mental model is a great way for improving your overall attitude at work and in your personal life, but isn’t that just having a positive attitude? Saying you ascribe to Hanlon’s Razor is a nice party trick and might make you feel like you have control over the negative thoughts that dance their way into your psyche. At the end of the day, you choose who and where to direct your effort and thoughts, as wasteful as it may be.

Let’s say you’re working on a group project and your group mate or colleague agrees to do the final formatting on the presentation you’ve been working for weeks on. Just a simple verbal agreement and trust between two teammates is all you need to know that the formatting will be done and you’ll look good in front of your boss come presentation day.

Your teammate sends you the presentation back and it’s not formatted at all and you don’t have time to fix it before the presentation. Is your teammate trying to sabotage you? Did they juts lie straight to your face? Your teammate is human, after all, and no amount of stewing or vitriol thrown at your teammate will make the situation better or complete the formatting task.

Why waste time thinking people are actively plotting against your downfall? Most people are too enthralled with their own lives to have the capacity to plan for these supposed roadblocks in your life. This is starting to get meta, but the question to ask yourself is whether the feelings and emotions are truly justified, or is there another rational explanation for what transpired?

Other Podcasts & Blog Posts

In the 2nd half of the episode, I talk about some episodes and blogs from other people I found interesting:

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] up from episode #77 about mental models, I wanted to take things one step further and tie mental models to one of my favorite shows. If you […]

[…] method created by Mark J. van der Laan. Eventually his team settled on an Occam’s Razor model to finding a model that would help them predict future fragile countries. This model was the a […]